Writing a “bare metal” operating system for Raspberry Pi 4 (Part 10)

Using multiple CPU cores

Instead of a background DMA transfer, I suggested that we might use a second CPU core to play the audio whilst our main core continues on. I also said it would be hard on the Raspberry Pi 4… and it is.

I wrote this code as I referenced Sergey Matyukevich’s work, for which I am very grateful. It did need some modification to ensure the secondary cores are woken up when the time is right. This code isn’t particularly “safe” yet, but it’s good enough to prove the concept in principle.

You’ll need to modify your config.txt file on your SD card to include the following lines:

kernel_old=1

disable_commandline_tags=1

arm_64bit=1

Perhaps the most important here is the kernel_old=1 directive. This tells the bootloader to expect the kernel at offset 0x00000 instead of 0x80000. As such, we’ll need to remove this line from our link.ld:

. = 0x80000; /* Kernel load address for AArch64 */

It also won’t lock the secondary cores for us on boot, so we will still be able to access them (more on this later).

Setting up the main timer

There is one other important piece of setup that we’ll need to take care of ourselves now - establishing the main timer. We add the following #define block to the top of boot.S:

#define LOCAL_CONTROL 0xff800000

#define LOCAL_PRESCALER 0xff800008

#define OSC_FREQ 54000000

#define MAIN_STACK 0x400000

LOCAL_CONTROL is the address of the ARM_CONTROL register. At the top of our _start: section we’ll set this to zero, effectively telling the ARM main timer to use the crystal clock as a source and set the increment value to 1:

ldr x0, =LOCAL_CONTROL // Sort out the timer

str wzr, [x0]

We go on to set the prescaler - think of this as another clock divisor equivalent. Setting it thus will effectively make this divisor 1 (i.e. it will have no effect):

mov w1, 0x80000000

str w1, [x0, #(LOCAL_PRESCALER - LOCAL_CONTROL)]

You should remember the expected oscillator frequency of 54 MHz from part9. We set this with the following lines:

ldr x0, =OSC_FREQ

msr cntfrq_el0, x0

msr cntvoff_el2, xzr

Our timer is now as we need it.

Booting the main core

We go on to check the processor ID as we always have. If it’s zero then we’re on the main core and we jump forward to label 2:. This time, we have to set our stack pointer slightly differently. We can’t set it below our code, because it’s at 0x00000 now! Instead, we use the address we defined earlier as MAIN_STACK at the top:

// Set stack to start somewhere safe

mov sp, #MAIN_STACK

We then continue to clear the BSS as always, and jump to our main() function in C code. If it does happen to return, we branch back to 1: to halt the core.

Setting up the secondary cores

Previously, we’ve unequivocally halted the other cores by spinning them in an infinite loop at label 1:. Instead, each core will now watch a value at its own designated memory address, initialised to zero at the bottom of boot.S, and named as spin_cpu0-3. If this value goes non-zero, then that’s a signal to wake up and jump to that memory location, executing whatever code is there. Once that code returns, we start looping and watching all over again.

adr x5, spin_cpu0 // Base watch address

1: wfe

ldr x4, [x5, x1, lsl #3] // Add (8 * core_number) to the base address and load what's there into x4

cbz x4, 1b // Loop if zero, otherwise continue

ldr x2, =__stack_start // Get ourselves a fresh stack - location depends on CPU core asking

lsl x1, x1, #9 // Multiply core_number by 512

add x3, x2, x1 // Add to the address

mov sp, x3

mov x0, #0 // Zero registers x0-x3, just in case

mov x1, #0

mov x2, #0

mov x3, #0

br x4 // Run the code at the address in x4

b 1b

You’ll notice that we’ve set our stack pointer elsewhere, and each core has its own designated stack address. This is to avoid it conflicting with activity on the other cores. We establish the necessary pointers to a safe memory area by adding the following to our link.ld:

.cpu1Stack :

{

. = ALIGN(16); // 16 bit aligned

__stack_start = .; // Pointer to the start

. = . + 512; // 512 bytes long

__cpu1_stack = .; // Pointer to the end (stack grows down)

}

.cpu2Stack :

{

. = . + 512;

__cpu2_stack = .;

}

.cpu3Stack :

{

. = . + 512;

__cpu3_stack = .;

}

Phew! That’s it for the bootloader code. If you use this new bootloader with your existing code, the RPi4 should boot and run as before. We now need to go on to implement the signalling required to execute code on these secondary cores which are now at our disposal.

Waking the secondary cores from C

Check out multicore.c.

Here we essentially duplicate two functions for each core:

void start_core1(void (*func)(void))

{

store32((unsigned long)&spin_cpu1, (unsigned long)func);

asm volatile ("sev");

}

void clear_core1(void)

{

store32((unsigned long)&spin_cpu1, 0);

}

The first, start_core1(), uses the store32() function (also in multicore.c) to write an address to our predefined spin_cpu1 memory location. This takes it non-zero, telling core 1 where to jump to when it wakes. Since we put it to sleep with a wfe (Wait For Event) instruction, we use a sev (Set Event) instruction to wake it again.

The second, clear_core1(), can be used by an executing function to reset spin_cpu1 to zero, so the core won’t jump again when the executing code returns.

More main()’s please!

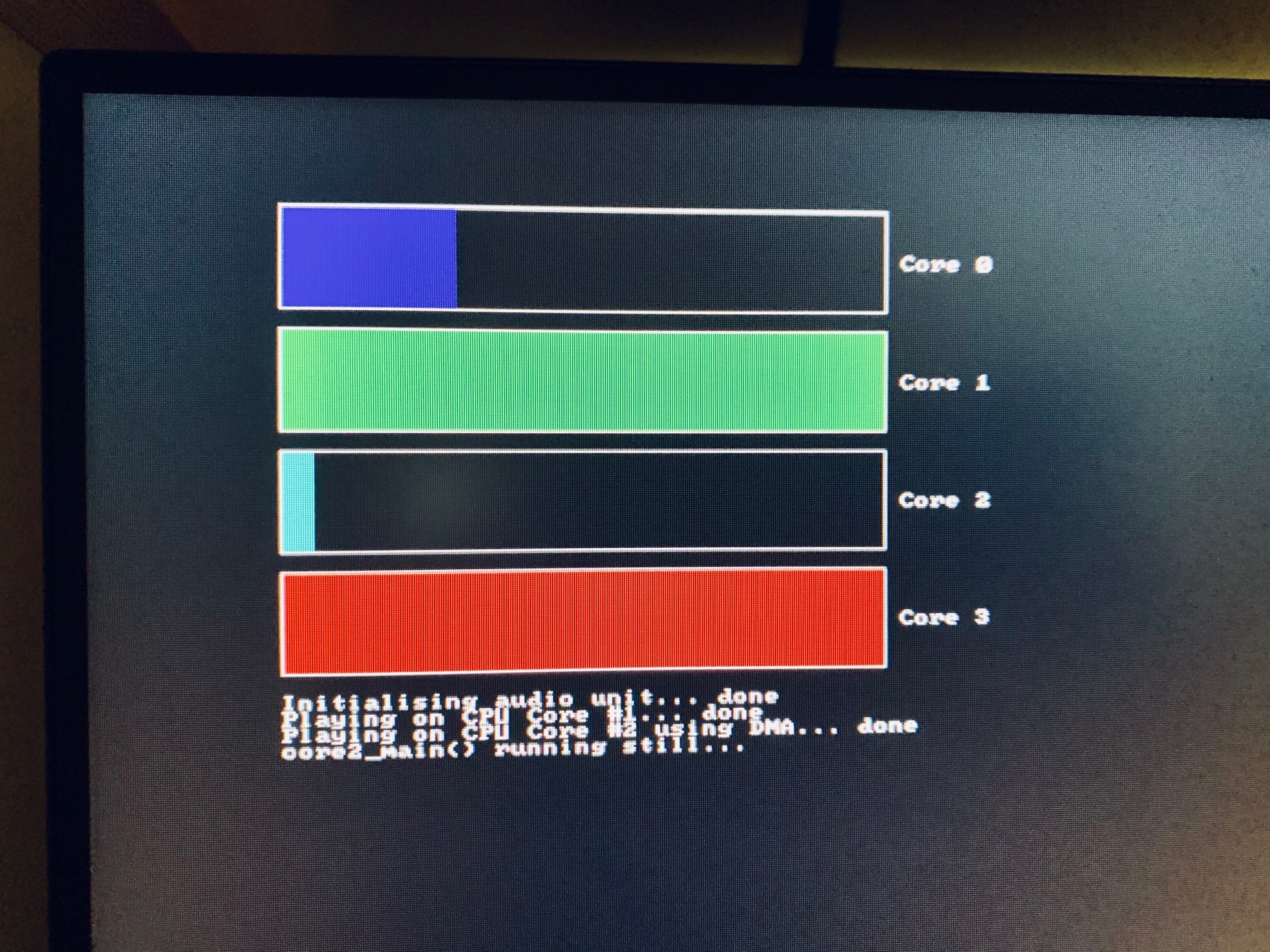

Finally, we look at kernel.c, where we now have a single main(), but also:

core0_main()- increments a progress bar every 1 second (roughly)core1_main()- has a two-step progress bar, playing an audio sample using the CPU at 50%, jumping straight to 100% when donecore2_main()- sets a DMA audio transfer, then increments a progress bar every half second (roughly), jumping to 100% as playback finishes- … and

core3_main()- increments a progress bar every quarter second (roughly)

main() is core 0’s entry point, which ultimately falls through to core0_main(), but not before it kicks off core3_main() and core1_main() by passing them to their respective start functions. When core1_main() finishes, it kicks off core2_main().

As you run this, you’ll see that these functions run in parallel on their respective cores. Welcome to symmetric multi-processing!

If all you see on boot is the rainbow screen, try first updating your firmware using rpi-update from Raspbian.

Coming up in part 11, we’ll put all of this work together for a multi-core version of our Breakout game.