Writing a “bare metal” operating system for Raspberry Pi 4 (Part 8)

Receiving Bluetooth data

So we’ve mastered advertising and we’re broadcasting data out into the World. But that’s only half the story! In this part, we’ll be exploring how to receive data from an external source. This is much more exciting as we can begin to use other devices as remote controllers.

In fact, my idea for this part is to control the Breakout game we wrote in part6 by receiving data from the trackpad on my MacBook Pro over Bluetooth! Neat, eh?

Building a Bluetooth Breakout controller

Let’s first build the controller code for broadcasting from the laptop. We essentially need to create a BLE peripheral in code.

We don’t need to build everything from scratch since we’re not on bare metal any more! I used the Bleno library, which is extremely popular for this kind of work. It requires some Node.js knowledge, but I didn’t have any before I started and so I’m sure you’ll be fine too.

Once you’ve got Node.js installed, use npm to install Bleno with npm install bleno. Because I’m on a Mac and running a recent version of Mac OS X (> Catalina), I needed to do this using these three steps instead:

npm install github:notjosh/bleno#inject-bindingsnpm install github:notjosh/bleno-macnpm install github:sandeepmistry/node-xpc-connection#pull/26/head

I used the echo example in the Bleno repository as my base code. This example implements a Bluetooth peripheral, exposing a service which:

- lets a connected device read a locally stored byte value

- lets a connected device update the locally stored byte value (it can be changed locally too…!)

- lets a connected device subscribe to receive updates when the locally stored byte value changes

- lets a connected device unsubscribe from receiving updates

You won’t be surprised to know that my design is for our Raspberry Pi to subscribe to receive updates from this service running on my laptop. That locally stored byte value will be updated locally to reflect the current mouse cursor position as it changes. Our Raspberry Pi will then be notified every time I move the mouse on my MacBook Pro as if by magic!

You can see the changes I made to the Bleno echo example to implement this in the controller subdirectory of this part8-breakout-ble. They boil down to making use of iohook, which I installed using npm install iohook. Here’s the interesting bit (the rest is just plumbing):

var ioHook = require('iohook');

var buf = Buffer.allocUnsafe(1);

var obuf = Buffer.allocUnsafe(1);

const scrwidth = 1440;

const divisor = scrwidth / 100;

ioHook.on( 'mousemove', event => {

buf.writeUInt8(Math.round(event.x / divisor), 0);

if (Buffer.compare(buf, obuf)) {

e._value = buf;

if (e._updateValueCallback) e._updateValueCallback(e._value);

buf.copy(obuf);

}

});

ioHook.start();

Here, I’m capturing the x coordinate of the mouse cursor and translating it into a number between 0 (far left of the screen) and 100 (far right of the screen). If it changes from the previous value we saw, we update the callback value (our Raspberry Pi only needs to know when the position has changed). As the callback value is updated, so any subscribed devices will be notified.

And we have ourselves a working, albeit a bit hacky, Bluetooth game controller! You can run it with the command node main.js, but it won’t do much without something to connect to it.

Connecting to our Breakout controller from the Raspberry Pi

main.js, when running, is sitting there broadcasting the Breakout controller’s availability publicly, using exactly the same techniques that our Eddystone beacon used. Our tasks on the Pi are now:

- to start listening (called “scanning”) for these adverts so we know where the echo service can be found

- to connect to the echo service, having found it

- to subscribe to receive its updates on cursor position

- to listen for these updates and do something upon receipt

Remember I mentioned that we’d discuss the run_search() function in part7-bluetooth? Well, this is exactly what it does. This time comment out the run_eddystone() function and let run_search() run whilst your echo service is running on the laptop. As you wiggle your finger on the trackpad, you should see the updates coming through on the Pi!

Instead of advertising, run_search() puts the Bluetooth controller into scanning mode (see links in part7-bluetooth to learn more about how this is done). bt_search() in kernel.c is then called repeatedly until it receives some specific advertising data - namely a notification of the availability of the echo service’s Service ID (hexadecimal number 0xEC00), as well as its broadcast name ‘echo’. If it sees both in the same advertising report then it assumes it’s found what it’s looking for. The originating Bluetooth Device Address is noted.

We send a connect() request to that address (LE Create Connection in the TI docs) and now call bt_conn() repeatedly until we’re notified that the connection has completed successfully. When this happens, we get a non-zero connection_handle. We’ll use this to identify communications from/to the echo service from now on.

Next we send a subscription request to the service using that handle in sendACLsubscribe() in bt.c. We tell it that we’re interested in receiving updates to its stored value (or “characteristic”). I actually did a lot of reverse-engineering to get to this code. ACL data packets over HCI are not widely documented. Have a read of this forum thread to see the kind of things I did to succeed. gatttool and hcitool on Raspbian turned out to be my very good friends!

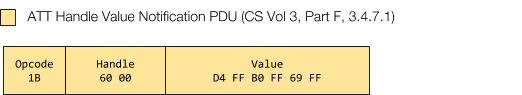

Finally, we call acl_poll() repeatedly to see if there are any updates waiting. The data comes to us in the form of an ACL packet, which identifies, amongst other things, the connection handle it was sent to/using (worth checking against our recorded handle so we know it’s for us) as well as data length and an opcode.

The opcode 0x1B represents a “ATT handle value notification” (ATT_HandleValueNoti in the TI docs). Those are the updates we’re looking for. In part7 we simply print the update to debug to show it’s been received.

The last mile

With this, it’s a good exercise to take part6 and part7 code and merge them to form a working Breakout implementation that’s controlled via Bluetooth! After all, that’s exactly how I ended up with the part8 code… If you get stuck, it’s all in my repo.

Good luck! Next time, we’ll look at adding sound to the gameplay…